Book Review

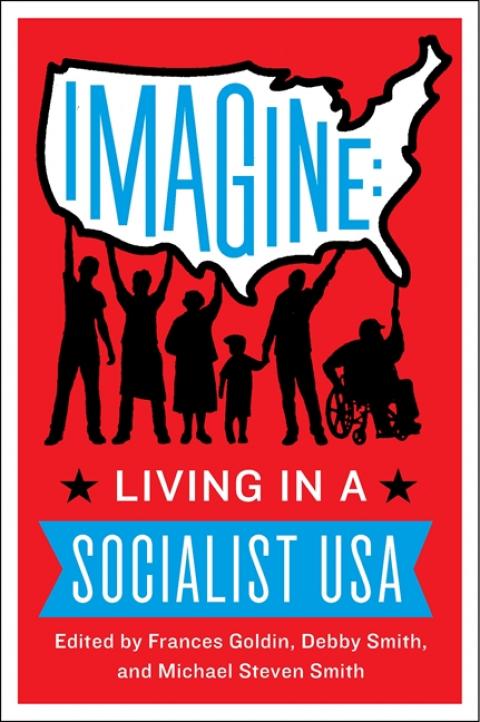

Imagine: Living in a Socialist USA, Edited by Frances Goldin, Debby Smith, and Michael Steven Smith (HarperCollins Publishers, NY)

Release Date: January 21, 2014

In her preface to Imagine: Living in a Socialist USA, Frances Goldin tells us that “ignorance about what socialism really is and how it could be realized here in our own country is appalling.” In an attempt to correct this misperception Goldin, joined by co-editors Debby Smith and Michael Steven Smith, has put together a collection of twenty-six essays, three speeches, two poems, and one short story by thirty-one writers. The book is divided into three sections. The first contains but one chapter titled “Capitalism: The Real Enemy.” The third has 10 chapters under the heading “Getting There: How to Make a Socialist America.” Most of the entries are grouped in the second section, “Imagining Socialism,” the heart of the book. These essays cover a wide range of topics such as the economy, housing, health care, drugs, education, art, housing, and the media.

In their introduction, the Smiths write: “This is a book of imagination, not utopian fantasy. What it envisions – what it hopes for – is eminently possible.” To emphasize this point, the Smiths note that socialism has been “done before – or more precisely, it’s been attempted.” But their brief analysis of why these attempts have fallen short is weak. The failure of the USSR is attributed solely to its beginnings as an “underdeveloped country ravaged by World War I” that had to endure an early invasion and subsequent embargo by capitalist nations. There is no mention that having survived those crises it managed to develop into a world economic power. Almost identical factors are cited to account for failed socialism in China, Vietnam, and Cuba. The Smiths do not mention the failure of socialism in other European states that were not initially “underdeveloped.”

This omission of other factors that likely contributed to socialism’s failure suggested to me an implicit belief on the part of the editors that the failed socialist model can still work. I was therefore eager to learn what the contributors might offer in the way of new ideas, especially in describing the essential feature distinguishing socialism from capitalism – the economic system. For this reason, and due to the constraints of space, I have focused on a few key chapters in this review.

“A Democratically Run Economy Can Replace the Oligarchy” is the first of two essays on a socialist economy. Ron Reosti’s central point is that we can “democratically design and control an economy that satisfies the needs and desires of the people.” He cites the success of “employee and community owned enterprises and co-ops” in the United States as “the best evidence that capitalists are not necessary” to have an efficiently run economy.

He maintains that “despite the destructiveness of corporate power . . . some enterprises of that size will continue to exist in a socialist economy. Their economies of scale will be beneficial, provided they are run democratically.” To support his contention that worker-control is feasible at this scale, Reosti claims that “even in large corporations the workers handle the day-to-day operations – not the owners, stockholders, and financiers.” This is a surprising – and misleading – statement. What about executives and managers? I thought back to my days as a production worker. There was never a shortage of bosses making clear who ran the show.

As further evidence that “large, publicly owned corporations” could “operate democratically, subject to a democratically determined central plan” in a socialist economy, Reosti cites the existing Social Security Administration, Veterans Administration hospitals, and public utilities. “Despite the government’s control of these programs,” he notes, “they have not established a dictatorship, and they are remarkably free of corruption.” Reading this, I wondered how workers at these entities might react. How much say, if any, do most government employees have in their employer’s operations? I spent over twenty years organizing and representing public employees. Many sincerely believed their workplaces were, in fact, dictatorships – a major motivation for joining unions.

As to being “remarkably free of corruption,” can VA hospitals be credibly described as meeting that standard? Remember the revelations of widespread mistreatment and abuse of patients in 2007? And what about the more recent exposures of bribe-taking by hospital administrators?

The specter of democracy hangs heavy over Reosti’s vision of a socialist economy. Other than the election of central planners for “limited terms” with “no power outside their office” he offers no blueprint –not even a sketch – of how democratic decision-making might actually work in an economy of 300 million people, a VA-sized entity of 300,000, or a workplace of 3000. Reosti does inform us that “many . . . social scientists . . . have described how such an economy could work. They differ about how decisions would be made, but they are unanimous that the decision-making process must be democratic.” Some concrete examples, and a mention of sources, would have been helpful.

In “The Shape of a Post-Capitalist Future,” economist Rick Wolff does provide a fairly detailed mechanism for democratic, worker-control. First, though, he offers a novel theory for the demise of 20th century socialism – the failure to eliminate what he describes as a four-part internal corporate structure. Under capitalism, this consists of (1) major shareholders who appoint (2) a board of directors to “determine what to produce and where to produce it” and that hires (3) “the workers who directly produce the goods and services,” as well as (4) “auxiliary” or “ ‘indirect’ workers: the managers and supervisors, clerks, and others who create the framework for the workers to produce profitably . . .”

But corporate boards are not known to make production decisions and they certainly do not hire the workers. Those decisions are delegated to the CEO’s, COO’s, and other highly-compensated executives who in turn hire HR specialists, managers, and so on. A five-part structure perhaps?

In any case, Wolff argues that “Soviet state enterprises largely retained” this structure. Corporate boards were replaced by a council of ministers; shareholders by “the Soviet government and Communist Party.” The “internal organization” of the workplace was fundamentally unchanged and the 20th century model of socialism failed.

Wolff imagines a new model “that would . . . insist on a radically different way of organizing the production, appropriation, and distribution of the enterprise’s surplus . . .” The “direct workers would function collectively as the board of directors, strongly influenced by the auxiliary workers.” Further, “this decision-making power” would be shared with “residential communities whose lives are interdependent with their enterprises. . .”

Wolff offers a hypothetical scenario for how worker/community control could function: “enterprises might . . . split their workweeks into two parts. Workers would do their regular jobs Monday through Thursday. . . On Fridays, all direct workers would meet to appropriate and distribute the surpluses . . . The auxiliary workers and community residents would join them to decide democratically who will receive what portions of the surplus and to make all the other basic decisions . . .”

Wolff sees this workplace reorganization as the key to restructuring the whole of society. “Socialist enterprises will begin a transition from today’s so-called democracy to the real thing,” he writes. “Workers who democratically design and direct their enterprises will likely demand parallel democratic participation in their communities’ governance.”

I see several problems with the above. Are the “direct workers” – those “who directly produce the goods and services” – really the majority in all corporate enterprises, as Wolff asserts? Why should the “auxiliary” workers – clerks, supervisors, others – be relegated to second-class status in the decision-making process? To which category do engineers and scientists belong? Who are “the direct workers” in private-sector universities and hospitals, for example? By Wolff’s definition, “direct workers” would include surgeons, nurses, professors, and research scientists. “Auxiliary workers” would include those in food service, clerical, custodial, and maintenance positions. Might this not foster a different kind of class division?

Also, the idea of hundreds or thousands of “direct workers” meeting “collectively as the board of directors” - then joined by the other workers and unknown numbers of community members – seems unworkable. And if, as Wolff envisions, the “direct workers” meet to collectively “appropriate and distribute the surpluses,” what will prevent the workers at one facility from compensating themselves more highly than those at others?

Closely related to economic reorganization is the future of technology. Clifford Conner’s essay is titled “What Science and Technology Could Accomplish in a Socialist America.” He too makes a number of dubious claims. For example, he writes that “new inventions and techniques” have always been “promoted as labor-saving devices” by capital. “But,” he asserts, “in practice, these innovations did not decrease laborers’ working hours or lighten their burden in any way.” Really? Mining? Agriculture? Factory work? The list of occupations in which technology has greatly reduced the need for hard labor is long. A shorter work-day was something workers had to fight for. But can it be denied that innovation has created the conditions that have permitted decreased labor-time without sacrificing productivity?

Another questionable claim is that “the experiences of the Soviet Union, China, and Cuba reveal that science and technology can not only exist without capitalist incentives, they can thrive.” But, it is commonly believed that one of the causes of the downfall of the USSR was the slow pace of technological change relative to the West. China’s more recent and impressive advances have taken place in the context of market reforms, exorbitant individual profits, and private property rights. Socialist Cuba, on the other hand, as Conner points out, has made great advances in medicine. But Cuba too has now moved to adopt features of capitalism as it lags in most other areas.

Conner devotes eight pages of his essay to describing the pitfalls of capitalism and extolling the virtues of the former Soviet Union, China, and Cuba. Only two paragraphs at the end address the topic at hand, “Imagining Socialism.” This was disappointing. I can think of no other area in which the imagination would have more room to roam.

A transition from capitalism to socialism would almost certainly be accompanied by changes in the law. In “Law in a Socialist USA,” Attorney Michael Steven Smith, one of the co-editors, advises us that “to envision what the law would become, we need to understand where it came from.” This leads to a lengthy discussion of the evolution of capitalist law, which I found to be unconvincing. Smith cites the book “Law and the Rise of Capitalism” as his source. Lawrence Kaplan, a professor of history, writing in the Marxist journal Science and Society, described that book as “an account of Western history which is seriously deficient.”

Smith’s discussion of the law – so critical, one would think, to any discussion of a socialist transition – is not only historically flawed, but lacking in specificity about the future. Like Conner, he devotes scant space to the topic at hand. He gives us one sentence to describe changes in the law in an initial phase of socialism: “Since commodity relations will continue to persist . . . as we make the transition from capitalism to socialism, our laws will continue to reflect bourgeois norms, however mitigated, because of unavoidable inequalities.” After that, sooner rather than later, “There will be no need for law as we know it. Human relations will become regulated more by custom, as they once were before the advent of class society.”

I had hoped this chapter would contain some discussion of the U.S. Constitution and its Bill of Rights. Smith writes that “The law we have now – contracts, property, corporate, trusts and estates, domestic relations, torts (injuries) – is based on the ownership of private property.” But that’s not all the law we have. There is also the law of individual rights. One of the major objections to socialism has been that it does not respect individual freedom. “Law in a Socialist USA” should have addressed that concern.

To the editors’ credit, the importance of democracy in a socialist USA is a theme that runs through many of the chapters. But this highlights what is perhaps the major weakness of “Imagine” – not a single chapter is devoted to what the political system might be like. What kind of democracy? What role for political parties? Would the division of powers between the three branches of government, and between the federal government and the states, remain as is? Would the senate be abolished and so on?

I was also struck by the relative scarcity of women contributors. One of the universal features of the so-called socialist states – extant and deceased – has been patriarchy. Indeed, as the trend among most capitalist nations has been toward more women holding key positions of power, such is not the case in China, Vietnam, Cuba, et al. This is disturbing and begs the question, Why?

Blanche Wiesen Cook – “Dignity, Respect, Equality, Love” – is the only contributor who addresses this concern, albeit tangentially. Her essay uses a remembrance of women who have contributed to the struggle for socialism to argue for the importance of women’s empowerment and equality both in a future socialist society and in the effort to achieve it.

A provocative essay co-authored by Mumia Abu-Jamal and Angela Davis addresses the vast injustices of the “prison-industrial complex.” They offer some creative solutions to this deep-rooted problem that could be incorporated into a socialist (or capitalist) USA.

The final section, “Getting There: How to Make a Socialist America,” includes a chapter by film-maker Michael Moore. Most of the works in this section are well-worth reading, as the authors suggest various possible paths to socialism (or social democracy). Some very interesting ideas are offered by Moore, retired autoworker Diane Feeley, Brecht Forum director Kazembe Balagun, and history professor Paul LeBlanc.

[Marc Beallor is a social justice activist and writer. He has worked as an organizer, staff representative, and regional director for the Ohio Association of Public School Employees (AFSCME) and the New York State Nurses Association. He was a member of the United Steel Workers at the American Metal Climax smelter in Carteret, NJ, the International Union of Electrical Workers at the Reliance Electric Co. large-motor plant in Cleveland, and the International Brotherhood of Teamsters.]

Spread the word