The noncompete agreements many employees are required to sign have drawn increasing attention in state legislatures—and even the White House—for their harmful impact on employees and the innovation economy. Yet noncompete reform legislation is often defeated through the lobbying efforts of incumbent businesses. In Massachusetts, reform opposition has been led publicly by the 70,000-employee tech giant EMC.

Now technology professionals at EMC are joining a labor organizing campaign, Noncompetes.org, to eliminate their noncompetes before Dell completes its massive leveraged buyout of EMC. The campaign is led by EARN, the Employee Association to Renegotiate Noncompetes, which was formed this spring to combat the negative impacts of noncompetes. It sees Dell’s impending acquisition of EMC as an opportune time for employees to press for reform prior to any transition.

Opponents of noncompete reform argue that they need noncompetes to protect their trade secrets. California companies, however, successfully rely on employee nondisclosure and nonsolicitation agreements to protect their intellectual property. Another reason companies may favor noncompetes is that they depress wages. According to the latest research, if Massachusetts adopted a California-like ban on noncompetes, wages for the average Massachusetts tech worker would increase by 7%.

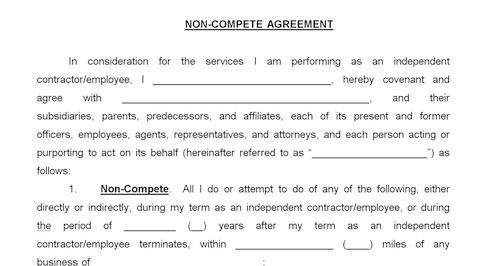

The very existence of noncompetes is often a surprise to union workers, whose contracts prohibit them. Noncompetes, which prevent employees from working for a competing employer after the termination of their employment, have been signed by 37 percent of U.S. employees at some point in their careers, according to a recent U.S. Treasury Department report. “That’s crazy. That’s like my ex-wife being able to prevent me from getting remarried,” one union member said of noncompetes.

Noncompetes place a particularly heavy burden on workers with specialized skills, especially tech workers, by limiting their ability to pursue new opportunities and participate in cutting edge technologies. And that, in turn, limits their ability to make the most of their education and training.

A couple of states, most notably California, ban employee noncompete agreements entirely. In fact, EMC employees cannot be bound by noncompete agreements in California, since they’re unenforceable in that state. The same holds true for EMC employees in India.

Other reform efforts have focused on providing workers with compensation in exchange for signing and abiding by a non-compete. This approach was recommended in the recent Treasury Department report, which noted that such consideration would compensate employees for the period of unemployment or underemployment imposed by a noncompete. This recommendation is embodied in the “garden leave” clause of Massachusetts’ proposed bill H.4323, recently released from committee (summary here). Garden leave clauses are a common industry practice in the U.S. financial industry. They’re mandated by law in China and parts of Europe, but Massachusetts would be the first U.S. state to require them.

Employee associations such as IEEE-USA, and high-tech innovators generally, support meaningful limits on noncompetes, often including their complete elimination. Their efforts, however, are often met with strong opposition from incumbent business interests wielding significant political influence. For example, in Utah a recent bill banning noncompetes had bipartisan state House and Senate committee support, as well as the support of Utah’s House Speaker. Yet incumbent businesses, including trucking companies with little proprietary technology to protect, successfully opposed the ban, and the bill that eventually passed simply imposed a one-year limit on the duration of an employee noncompete. One year is a very long time for a worker to remain unemployed.

Some tech workers are therefore considering other ways to protect themselves against being forced to sign noncompetes. One strategy is unionizing. Since a noncompete agreement is a mandatory subject of bargaining, workers have the right under the National Labor Relations Act to organize and negotiate to eliminate noncompetes. They can even engage in strikes or other protest activity to persuade the employer that the cost of insisting on a noncompete is too high. Tech workers, however, may not feel a need for the comprehensive protections provided by a union such as the IFPTE, and they may not be interested in participating in job actions as contentious as strikes. There is interest, though, in work actions occurring outside of daytime work hours, for example limiting work-related activities during specific evenings or weekends.

An acquisition is an opportune time for employees to organize. An acquirer’s investors and lenders may be concerned that once an employee association or union is certified to negotiate over noncompetes, other labor issues such as severance terms could be subject to negotiation. An acquirer may also be concerned that the employee association could expand to include their own employees following the acquisition. These reasonable concerns could provide additional leverage to the employees seeking to eliminate their noncompetes.

EMC’s employees are using this leverage in EARN’s campaign to eliminate their noncompetes. The proxy statement/prospectus filed on 6/6/16 by Denali, Dell’s acquisition vehicle, indicates that EMC has represented to Dell that there’s no labor organizing activity among its employees. That statement ignores EARN’s organizing effort.

Kevin Johnson is Founder of Common Commute, a commute sharing platform. James Bessen is an economist and a lecturer at the Boston University School of Law. He is the author of the book Learning by Doing: The Real Connection Between Innovation, Wages, and Wealth. Michael J. Meurer is Professor of Law at Boston University School of Law, and co-author with James Bessen of Patent Failure: How Judges, Bureaucrats, and Lawyers Put Innovators at Risk. Catherine Fisk is Chancellor’s Professor of Law at the University of California, Irvine and an OnLabor Senior Contributor.

Spread the word