ABINGDON, Va. — Deborah McCroskey’s farm rests on the gentle slopes of what locals here call McCroskey Mountain, 188 acres in Virginia’s southwest corner that have nurtured fields of tobacco and herds of cattle for at least four generations of McCroskeys. But on Sept. 14, 2015, the same farm that provided a living for her forbearers took her father’s life.

Luther McCroskey, 75, had come home from a dental appointment and climbed into a 1979 Long tractor to clear a bit of land. After night fell, his body was found pinned under the flipped tractor on the far side of the hill — one of 401 people to die in farm-related accidents that year.

“The thing people couldn’t understand is that Dad had done this since he was 14 years old,” Deborah McCroskey said. “They always say you’ll get killed close to home and when you least expect it.”

Farming is one of the most dangerous occupations in America, with 22 of every 100,000 farmers dying in a work-related accident. Farmers are nearly twice as likely to die on the job as police officers are, five times as likely as firefighters, and 73 times as likely as Wall Street bankers.

"Down in here when I was growing up, we had a funeral practically every week for someone that had gotten killed in an accident,” McCroskey said. “That was my greatest fear from the time I was a little kid, that my father would have an accident on the tractor. And of course, it did come to pass."

Farming death rates may be high, but the injury rates are even higher. In 2014, the most recent year for which data are available, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimated there were 58,000 adult farm injuries — nearly 6,000 more than the number of U.S. soldiers wounded in all the years since 9/11.

Many of those injuries last a lifetime, driving up disability rates among rural Americans, who are 50 percent more likely to have some form of disability than their urban counterparts. Also contributing are high rates of injury in other professions rooted in rural areas, including logging, fishing and trucking.

Edmon de Haro for POLITICO

In fact, the jobs that provide the way of life in America’s iconic farms, fisheries and forests also tend to be the most dangerous in the country. As a result, occupational safety — or the lack of it — is a major and largely unexamined contributor to a cycle of disability, poverty and chronic poor health that makes life difficult for millions of rural Americans.

“It increases depression and isolation, and that further exacerbates health conditions,’’ said Tom Seekins, director of the Research and Training Center on Disability in Rural Communities at the University of Montana. "It can be a really vicious cycle.’’

IF YOU HAVEN'T lived in a farming community you probably didn’t know small farms were such dangerous places. The yeoman farmer occupies a hallowed place in the American story, part of the reason farms are excluded from virtually all workplace safety requirements. Indeed, the federal hands-off approach to farms goes even further: Congress won’t let federal agencies keep precise injury records for small farms, and the CDC estimate of 58,000 injuries may understate the problem. Small farms have been exempted from federal oversight for so long that it’s virtually impossible for anyone — regulators, lawmakers, even the farmers themselves — to understand fully the epidemic of workplace injuries and deaths that has plagued rural America for at least a century.

“Some of this data is worthless,” said Bill Field, a farm safety researcher at Purdue University.

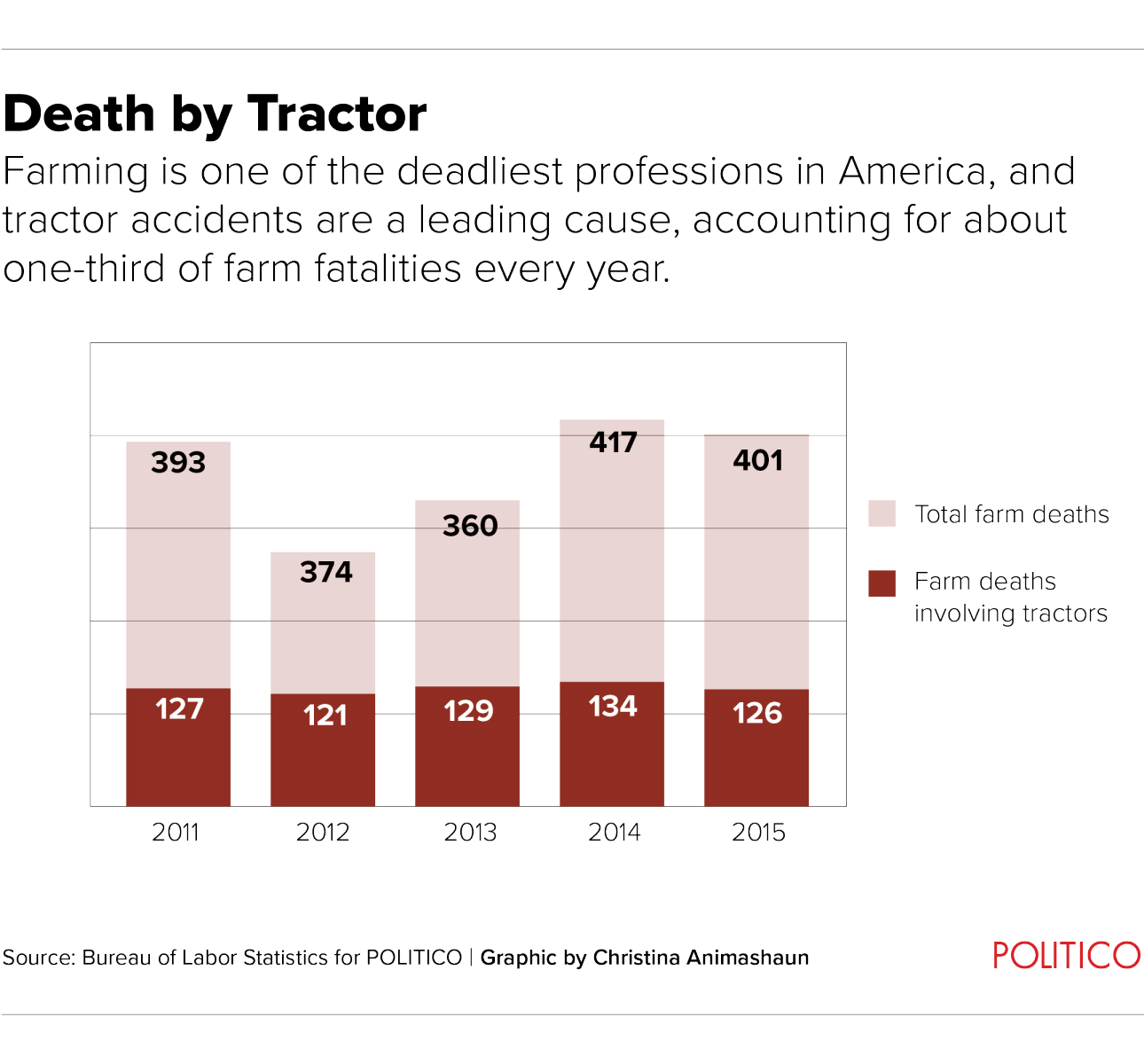

Farming is the rare industry rendered more dangerous — rather than less — by mechanization. In 1914, the Waterloo Gasoline Traction Engine Co. released the Model “R” single-speed, the first commercially produced gasoline powered tractor in the United States. Tractors revolutionized crop production, making the U.S. a prolific producer of corn, grain and soybeans. The human cost, though, was high. Today, nearly one-third of all agriculture deaths involve tractors, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics data compiled for POLITICO.

Edmon de Haro for POLITICO

More than 80 percent of tractor deaths are preventable with a simple rollover protection device — basically a metal bar bent into an inverted U-shape that sits behind the driver. All modern tractors are equipped with them. The problem is that most tractors used on small farms aren’t new. Farmers are a frugal bunch, and many, like Luther McCroskey, keep the same models for decades, replacing parts as needed. As a result, fewer than 60 percent of tractors in use in the U.S. have rollover protection, according to the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

New tractor models are getting safer in other ways. Instead of rollover bars, many have full-fledged cabs, enclosures that protect the drivers. Tractors also now often have seat belts, and wheel structures that provide better stability. Researchers at Penn State are working on computer-based technology that would alert the driver when a tractor starts to become unbalanced. That research is still in the early stages, though, and farmers don’t seem to be clamoring for the technology.

“There’s not much incentive for the tractor companies to do this when there’s no demand for the thing,” said Dennis Murphy, a Penn State agricultural safety specialist. “It’s a legit argument, but I would like to see the tractor not turn over in the first place.”

Vehicle accidents also contribute heavily to mortality on farms, in part because the job requires farmers to drive long distances on unsafe roads. Other dangers include falls from roofs and multi-story barns, trampling by farm animals, suffocation in grain silos, and exposure to toxic pesticides and herbicides.

Farms are especially dangerous for children. From 2003 to 2010, there were more deaths for agriculture workers younger than 16 than there were for workers of the same age in all other industries combined, according to the National Children’s Center for Rural and Agricultural Health and Safety. The vast majority of these minors were family members and therefore not subject to labor laws.

“If it was a construction zone, it would be fenced in and you wouldn’t be allowed in without a hard hat,” said Barbara Lee, director of the center. “Farming is just as dangerous [as] construction, but there are no restrictions.”

WHY DON'T AMERICANS push for better safety on small farms the way they do in other industries? One reason is reverence for the agrarian ideal. “Those who labor in the earth are the chosen people of God,” Thomas Jefferson once wrote. Teddy Roosevelt, the Manhattan-raised son of a plate-glass importer, said, farmers “form the basis of all the other achievements of the American people.”

For decades, groups like the American Farm Bureau Federation have lobbied Congress successfully to exempt small farmers from most workplace regulations. A perennial rider to the Occupational Health and Safety Administration budget bill prevents the agency from inspecting or enforcing violations on any farm with fewer than 11 employees — a loophole that exempts up to 88 percent of all U.S. farms. The rider also prevents OSHA from tallying nonfatal injury data on small farms, and the Bureau of Labor Statistics doesn’t keep reliable data on farm size.

In other occupations, labor unions often press for workplace protections. But the 1935 National Labor Relations Act, created to protect workers’ right to form a union, exempted agriculture workers. So did the 1938 Fair Labor Standards Act, which regulates wages and hours and restricts the use of child labor. These New Deal laws had to exempt farm workers to secure support from conservative southern Democrats, who may have been motivated in part by racism.

“Southern legislators basically said, ‘We employ African-Americans on our farms, and we are not going to give them the same rights as other workers in this country,” said Arturo Rodriguez, president of United Farm Workers Union, which has fewer than 10,000 members.

Land grant universities have tackled the farm safety problem on a small scale, creating a patchwork of state-level farm safety specialists. In 1975, Congress appropriated $15,000 —upping it to $20,000 a year later — to each state to support the farm safety specialists’ work. But funding was redirected in the years since; only 11 farm safety centers are left, with a combined budget of $25 million, and much of their mission is devoted to research instead of outreach to farmers.

“For the most part, they only do it in the state in which they are located, so [it’s] not as far-reaching as it used to be,” Lee said. The Agriculture Department, for its part, has a program to help disabled farmers as well as provide some small grants for youth safety, but it does little in the way of injury prevention.

Edmon de Haro for POLITICO

“Small is beautiful,” the British economist E.F. Schumacher famously observed, but in agriculture, bigger is safer. CDC surveys demonstrate that big factory farms with hired help are typically much safer than smaller, more traditional farms. A 2008 CDC study found that tractor rollover protection systems were most prevalent on farms with $100,000 in sales or more. And more recent BLS data show that 69 percent of workers who died on farms between 2011 and 2015 were self-employed.

But the vast majority of U.S. farms remain family-owned operations, according to the Agriculture Department’s farm census. Eighty-eight percent of all U.S. farms are classified as small by USDA with revenue of less than $350,000, and many farmers also work other jobs to get by. Meanwhile, large farms with incomes of $1 million or more produce more than half of all vegetables and dairy. On small farms, owners rely on family members to work the land, who aren’t counted toward the 11-employee threshold needed to trigger OSHA oversight.

“As you get more employees, you take on more of a management structure, and you start looking like more industrial employers and, therefore, you come under safety regulations,” Murphy said. “As you get bigger, you get new farms that tend to be more safe.”

Small farmers are also strong-willed. Nobody loves being regulated by the government, but small farmers hate it more than most. Many see it as an affront to a way of life in which skills are passed down from generation to generation. And in an industry where weather determines success and failure, farmers are accustomed to dealing with risk.

“One of the biggest things we hear from our members across the country is [the] creeping of overregulation,” said Kristi Boswell, director of congressional relations for the American Farm Bureau Federation. “When they show up on the farm, it’s always an enforcement action — it’s not positive.”

Thus when the Labor Department proposed in 2011 a regulation banning children younger than 16 from operating tractors and those younger than 18 from working in silos, feed lots, and stockyards, it prompted a political uproar — even though the rule exempted children who worked on their parents’ farms. Eight months later, with the 2012 presidential election fast approaching, DOL withdrew the regulation and pledged not to reintroduce it for as long as Barack Obama was president.

Debbie Berkowitz, a senior policy adviser at OSHA under the Obama administration, recalled a push during her tenure to allow the investigation of deaths on farms. That also ran into a brick wall, though OSHA wasn't seeking more enforcement power.

“If you’re in a government agency and you’re trying to think about how to regulate farmers,” Berkowitz said, “you’re not going to get past thinking about it before they’re up on Capitol Hill lobbying like you’re trying to shut them all down. It’s like nothing I’ve ever seen.”

OSHA tried to start inspecting grain bins, which pose dangers of asphyxiation, in 2013. Again, the political reaction was fierce, with Sen. Mike Johanns (R-Neb.) declaring that “farmers know better than bureaucrats how to keep their employees and family safe.” Here, too, OSHA backed off.

Even Deborah McCroskey, who 19 months after her father’s death discusses the details of with remarkable fortitude, doesn’t support requiring the kind of safety equipment that could have saved his life.

“You have to understand a lot of small farmers just get by, you know, little by little, just like somebody working paycheck to paycheck,” she said. “If you put a lot of standards that would cause them to have to go out and buy all new equipment, they couldn’t do that.’’

In her mind, rural safety and poverty are linked, but in a different way: Forcing farmers to follow safety regulations, she said, would do more to put farms out of business than actually make them safer.

“Then they wouldn’t have any income,” McCloskey said. “It would just be a burden on society in a different way.”

Ian Kullgren is a reporter for POLITICO Pro’s Employment and Immigration team.

Spread the word