When Chicago Public Schools announced plans to close their neighborhood elementary school in March 2013, Lettrice Sanders and her children protested the proposal together.

Sanders, the president of the local school council at Emmet on the city’s West Side, became a familiar face in the media. “My momma, when she talked on the news, she was fierce,” her 16-year-old daughter, Brittany, recalls.

Lettrice and her husband, Kenneth Sanders, didn’t finish high school. She wouldn’t let the closures disrupt their children’s education.

But Emmet and 48 other elementary schools closed in an unprecedented decision for Chicago and any district in the nation. Sanders had a hard time finding another quality school for her children in Austin, the majority African-American neighborhood where they lived.

She had other concerns too. The family of seven was squeezed into a two-bedroom apartment because that was all they could afford. And that year, gunfire killed or injured nearly 60 people in Austin.

So in August 2013 Kenneth Sanders decided it was time to go.

The family packed their bags for Gary, Indiana, a predominantly black city where the schools struggled academically and financially, but Sanders could afford a house for his children in a safer neighborhood.

“I knew coming to a new state would be a new start for us all, and it was,” he said. “Most of us, no matter how bad we came up… wanted our kids to live better. That’s something I wanted for them.”

Chicago was once a major destination for African-Americans during the Great Migration, but experts say today the city is pushing out poor black families. In less than two decades, Chicago lost one-quarter of its black population, or more than 250,000 people.

In the past decade, Chicago’s public schools lost more than 52,000 black students. Now, the school district, which was majority black for half a century, is on pace to become majority Latino. Black neighborhoods like Austin have experienced some of the steepest student declines and most of the school closures and budget cuts.

A common refrain is that Chicago’s black families are “reverse migrating” to Southern cities with greater opportunities, like Atlanta and Dallas. But many of the families fleeing the poorest pockets of Chicago venture no farther than the south suburbs or northwest Indiana. And their children end up in cash-strapped segregated schools like the ones they left behind, a Chicago Reporter investigation found.

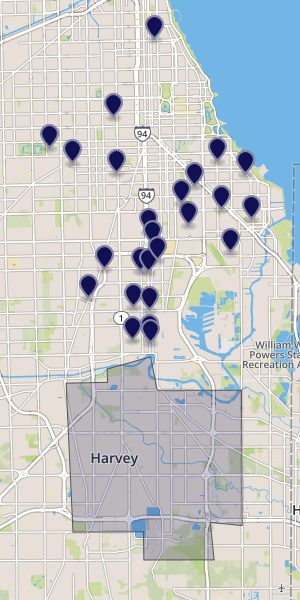

Three out of four CPS students who transfer into Thornton Township High School District 205 and its nine feeder elementary districts come from the city’s most segregated, low-income schools, the Reporter’s analysis found. This map shows CPS schools with the highest transfer volume to Thornton-area schools are primarily located on the city’s South and Southwest sides. The south suburban school districts have collectively enrolled more than 3,000 former CPS students since 2009. The state says all 10 districts in this boundary need significant additional funding to meet the needs of students. © Mapbox © OpenStreetMap

About 15,000 students from the city’s predominantly poor and African-American schools transferred out of CPS over the past eight academic years, yet remained in Illinois, according to an examination of tens of thousands of state transfer records. About one-third enrolled in school districts that are both majority poor and majority black.

The Reporter observed this trend continue in northwest Indiana. A public records request to East Chicago public schools, for example, revealed nearly 400 African-American CPS students had transferred into the district since 2010. The overall number of Chicago transfers to northwest Indiana schools is likely much higher, but record-keeping inconsistencies make it difficult to determine precise numbers.

Often, the receiving school districts in Illinois and northwest Indiana were chronically underfunded. Research shows poor black students in Illinois perform worse academically in such districts compared with Chicago.

Janice Jackson, the district’s interim CEO, recalls talking to a West Side principal who was “baffled” when students transferred to lesser-quality schools outside the city. The issue needs to be studied more, she said.

“It’s not one thing that drives any of this,” says Jackson.

A spokeswoman for Mayor Rahm Emanuel said his administration is taking steps to keep African-Americans in the city. “Mayor Emanuel has led several major initiatives to invest in our youth, support local businesses and create jobs in neighborhoods across the city,” Lauren Markowitz said in a statement. She pointed to expanded mentoring and jobs for African-American youth and investments in businesses and shopping corridors on the predominantly black South and West sides.

But some academics blame city officials for making it harder for poor African-Americans, in particular, to live in Chicago: They closed neighborhood schools and mental health clinics; failed to rebuild public housing, dispersing thousands of poor black families across the region, and inadequately responded to gun violence, unemployment and foreclosures in black communities.

“It’s a menu of disinvestment,” says Elizabeth Todd-Breland, who teaches African-American history at the University of Illinois Chicago. “The message that public policy sends to black families in the city is that we’re not going to take care of you and if you just keep going away, that’s OK.”

Chicagoans flee to a hollowed-out Gary

PHOTO BY JOSÉ ALEJANDRO CÓRCOLES

The Sanders family moved from a two-bedroom apartment on the West Side of Chicago to a single-family home in Gary, Ind., in 2013.

When Brittany first moved to Gary, the abundance of abandoned buildings surprised her. “It looked deserted,” she said.

Real-estate agents once marketed Gary as the “city of the century.” As home of the world’s largest steel mill, Gary employed tens of thousands of steel workers.

But in the 1950s and ‘60s, steel factories closed or modernized. Mass layoffs followed. Soon after, Gary elected its first African-American mayor and many white residents fled. Now, tens of thousands of buildings are vacant or blighted.

The Sanders family and other black Chicagoans have sought refuge in a hollowed-out city.

Northwest Indiana is the top destination for African-Americans who leave Cook County but stay in the greater Chicago area. Since Brittany arrived in Gary, her grandmother, uncle and great-uncle have moved there, too.

Denise Comer Dillard, a lifelong Gary resident and the board president of a local charter school, first noticed the influx of cars with Illinois license plates in the 1990s and 2000s as Chicago tore down its public housing. “We had situations that it almost looked like locusts,” she said.

Though enrollment in Gary’s public school district is declining, it’s taken in more than 1,300 black students from out of state in the last four years, records show.

“I’ve never seen anything like this,” says Terrance Little, the principal at the high school that Brittany and her 17-year-old brother, Ken, attend. “They transfer out just as quick as they transfer in… The kids that are here are so accustomed to kids moving back and forth.”

At school, reminders of Chicago are everywhere. Brittany’s closest friend is a transplant from the South Side. Another classmate transferred in this fall from a charter high school in North Lawndale run by Chicago’s Noble network. Ken has a classmate who transferred in from a Noble high school in Pullman. Little, who requires every transfer student to meet with him, estimates 10 of every 100 out-of-district transfers to his school is from Chicago.

“Now, it’s basically Chicago,” said Terry Flowers, who moved to Gary to be closer to family in 2000 after living in Englewood and Roseland. Her son and younger brother attend high school with Brittany and Ken. “Everyone from Chicago is here.”

Influx of poor black students in suburban schools

As African-American families leave Chicago, the percentage of poor black students in the suburbs has grown dramatically, straining already cash-strapped school districts.

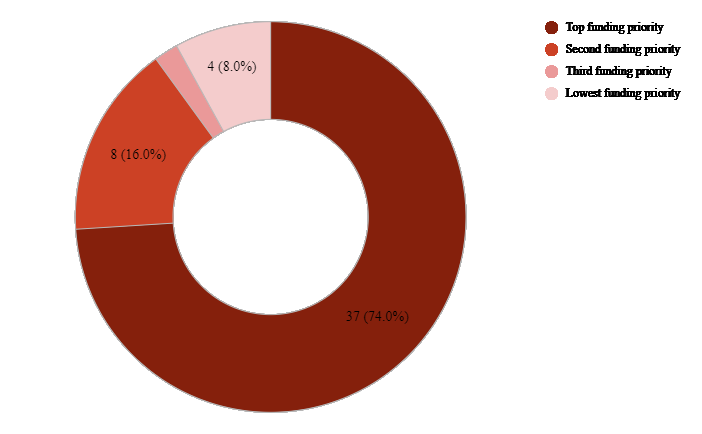

The Reporter looked at the 50 Illinois school districts most impacted by transfers from Chicago’s predominantly poor, black schools. Most districts were among the worst-funded in the state and have been shortchanged even more than CPS. (After years of debate, lawmakers overhauled Illinois’ school funding law earlier this year. To correct inequities, the state soon will send more money to districts with higher-need students.)

Three-quarters of the 50 Illinois districts most impacted by transfers from predominantly poor, black Chicago schools are also in dire need of more state education funding. Source: Chicago Reporter analysis of Illinois State Board of Education data

High-poverty districts in northwest Indiana that took in many CPS transfers have also seen their budgets slashed in recent years after lawmakers rejiggered the state’s school funding formula and also spent more on charter schools and private-school vouchers.

“If poverty is growing in their community and their property taxes and other budgets are stretched or declining, that makes it even harder to find the resources to address the need,” said Elizabeth Kneebone, who has researched suburban poverty extensively for The Brookings Institution.

In the south suburbs, the nearly all-black Dolton School District 149 has taken in hundreds of transfers from Chicago’s low-income black schools in recent years. Officials say the high transfer rate makes it hard to know how many teachers the small district of 2,800 needs. On top of that, the level of financial need has intensified with few new resources. Fifteen years ago, the district was about two-thirds low-income, but now nearly every student is poor. The students could be dealing with health or emotional issues. And many move around a lot, which causes children to fall behind academically.

“We need as much attention as the city schools because we have the same kinds of problems,” said Jay Cunneen, the former superintendent who now advises the district on its finances. “We’re overwhelmed by some of the needs the kids bring in.”

Gary Orfield, who co-directs The Civil Rights Project at the University of California, Los Angeles, says attending poor segregated suburban schools can pose more challenges for students.

“Poor minority kids and families who end up in declining or dying suburbs are worse off in terms of the fact that they’re very far away from where the economic growth is taking place,” Orfield says. “They may be 30 miles away from where a really good job market is with almost no workable public transportation.”

Some of the former Chicago students also end up in farther-flung suburbs.

Danville School District 118 is about 150 miles from downtown Chicago and it, too, has taken in hundreds of CPS students from segregated black and poor schools. Just over half of all students were considered low-income 15 years ago, now more than three-quarters are. That’s brought with it a host of additional student needs.

The district recently hired specialists from Lurie Children’s Hospital in Chicago to teach school staff about working with traumatized students and invested more money into summer school for struggling kids.

“Our children, they were hurting,” said Superintendent Alicia Geddis. “We needed to retool.”

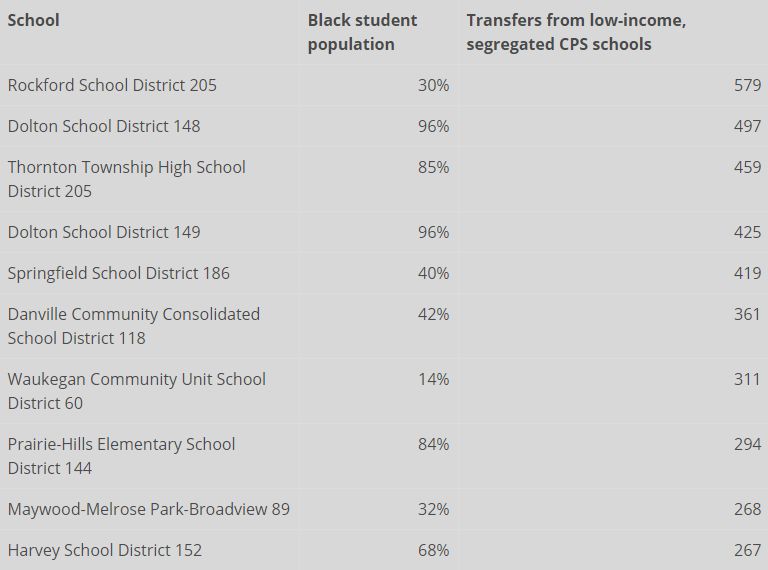

The 10 school districts listed above took in the most transfers from poor black CPS schools over the last eight academic years. They all meet the federal government’s criteria for “high-poverty” districts based on the income levels of their communities.

Gary school district facing similar challenges

PHOTO BY JOSÉ ALEJANDRO CÓRCOLES

Two of the six children in the Sanders family attend West Side Leadership Academy in Gary, Ind. If a proposed closure is approved, West Side would become the only high school run by Gary’s public school district.

Though Gary has its share of gun violence, the Sanders family feels safer in their new neighborhood than they did in Austin. It’s quiet and close to a local university and shopping.

“You can just walk down the street and ain’t nobody going to mess with you,” Brittany said.

Kenneth Sanders got a loan from a friend to purchase a cream-colored, single-family home for just over $13,000 — a deal after the previous owner foreclosed on the property. The house is much bigger than the family’s old Chicago apartment, where they used to hang a curtain in the living room to create an extra bedroom.

Sanders started a business breeding German shepherds. On Facebook, he posts photos of his 12-year-old daughter, Yasheica, caring for the dogs. It’s a significant departure from how he earned money in Chicago, where he sold cocaine for years. His turning point came in 2010, while sitting in Cook County Jail following an arrest for possession of marijuana and a gun.

But even though there’s a lot the Sanders family likes about Gary, they’ve seen the schools face significant challenges.

For the first time in Indiana’s history, state education officials took over Gary’s public school district this year. The state-appointed emergency manager says Gary’s schools need to be cleaner, safer and more academically challenging.

The city’s public schools fell deep into debt as students moved out of Gary or transferred to charter schools — taking state and federal education dollars with them. Even Dillard, the charter board president, says charters squeeze the district financially. “For us to have as many charter schools as we do in Gary,” she said, “it’s ridiculous.”

The budget crunch has manifested in large and small ways for students. Brittany carries hand sanitizer at school because the girl’s bathroom is often out of soap. Yasheica shares most of her textbooks with classmates because there aren’t enough. Brittany, Yasheica and their younger brother, Kentrel, had to transfer to an all-boys school when their elementary school’s old, faulty boiler broke and the school was shuttered for 17 months.

The Sanders family hasn’t been able to escape school closures in Gary, which has shut down buildings and laid off teachers in recent years to save money. When Ken’s old middle school closed, Yasheica’s elementary school took in the displaced kids. Just recently, Gary’s emergency manager put a popular arts high school on the chopping block.

Brittany and Ken’s principal says closing schools is a bigger deal in Chicago than Gary, because students in the smaller city often know one another before merging schools. But Brittany disagrees. She says it’s still disruptive for students.

“They’re just shutting down all these schools in these poor black communities. And it’s messed up,” Brittany said. “It worked out for me. [But] some of the kids probably can’t move, they’re just going to be stuck.”

“We need our education”

Brittany Sanders, 16, and her brother, Ken Sanders, 17, get ready for school

One day in October, Brittany and Ken rode the bus to West Side Leadership Academy, their nearly all-black high school. Brittany wore her long braids pulled into a ponytail and her school uniform: a navy blue shirt and khaki pants. Ken, who is tall with glasses, like his father, wore his crisp navy blue JROTC uniform with gold buttons.

The siblings like some aspects of their high school, including the JROTC program, their friends, the sports programs and many supportive teachers. But they both see ways they aren’t being challenged.

In his career prep class that day, Ken practiced his public speaking and wrote about the steps he needed to take to be a better leader. (“Being on time more,” was one). But after students finished their work, the teacher let them play tic-tac-toe for 20 minutes. “That gets boring sometimes,” Ken admits.

His English literature class made its weekly trip to the computer lab, where students clicked through exercises from a reading program, reviewing basic parts of speech. “It’s for babies,” Ken said. He especially hates that the female voice in the program talks “like we’re slow.”

Brittany and Ken have had a long-term substitute — one of dozens in the district — teaching their science classes. The sub sometimes passes class time by reading aloud long passages from the textbook. “She told us she’s learning right along with us,” Ken said.

Brittany wants to be a neurosurgeon, so having a qualified biology teacher was especially important to her. A few weeks ago, she co-wrote a letter to her school’s principal and assistant principal asking them to fix the problem. About 60 of her classmates, including Ken, signed it. Watching her mother stick up for her children’s education emboldened Brittany to write the letter. (Lettrice Sanders had a stroke two years ago and is still working to regain her speech.)

Brittany and Ken’s principal says the school advertised the opening for a science teacher but no one applied. It’s hard to attract top talent, he said, because Gary schools pay less than Chicago and other nearby districts. In the meantime, a veteran science teacher is helping the sub develop her lessons, though Brittany and Ken say the quality of instruction hasn’t improved.

“It feels like they brushed it to the side.” Brittany said. “We need our education.”

While Lettrice Sanders thinks Gary’s schools are worse than the ones in Chicago, Kenneth Sanders isn’t so sure. He says his 7-year-old daughter, Natalie, who started school in Gary, reads better than her siblings did at her age. “I regret not coming here earlier,” he says.

But even though his oldest children are about to graduate, he hasn’t stopped looking for better school options. He knows exactly where the boundary for a higher-performing school district ends—just a few blocks from his house. If only he could afford to move there.

_________________________________________

Kalyn Belsha is a reporter for The Chicago Reporter. Email her at kbelsha@chicagoreporter.com and follow her on Twitter @kalynbelsha.

Want more stories like this?

Get the latest from the Reporter delivered straight to your inbox.

Subscribe to our free email newsletter.

Spread the word