It is worth remembering, particularly right now, that High Fidelity was never just a story about record store nerds ranking their days away. Part of what made Nick Hornby’s 1995 novel such a hit, leading to a 2000 movie adaptation, was its uncensored view into the psyche of stunted, self-pitying, supposedly sensitive straight men who obsess over stuff. This fundamental male-ness was well-noted in reviews at the time. “Hornby’s books reveal a fascination with the sheer voodoo of what so often passes as masculinity: the weird ritual facts, the useless objects...” wrote The New Yorker, while lad mag Details was a bit blunter: “Keep this book away from your girlfriend—it contains too many of your secrets to let it fall into the wrong hands.” Those secrets include a deep fear of sexual inadequacy, including a passage where the record-store owner protagonist Rob self-deprecatingly longs for his father’s era, because back then a man wasn’t expected to make a woman cum. There’s another, more famous part where this same middle-aged man feels the need to warn other men that women don’t wear sexy underwear 24/7.

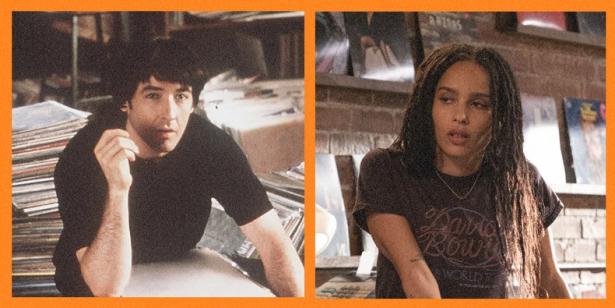

Hornby’s book is laden with Rob’s interior monologues, which are boiled down to a few key philosophies delivered straight to the camera by John Cusack in the movie: There’s the link between being sad and loving pop music (“What came first, the misery or the music?”), the rules for properly sequencing a mixtape, and the guiding principle that you are what you culturally consume.

The rom-com format also emphasizes Rob’s quest to track down his “Top 5 All-Time Most Memorable Heartbreaks,” starting with a girl he made out with for two afternoons in middle school, who apparently married the next boy she kissed. Later, Rob meets up with his high school girlfriend and asks why she slept with another guy so quickly after they broke up, since she was such a prude with him. She reminds Rob that he actually broke up with her and reveals that she was “too tired to fight [the other guy] off, and it wasn’t rape, because I said OK, but it wasn’t far off,” adding that she didn’t have sex for many years afterward. To which Rob responds, quoting the book verbatim, “That’s another one I don’t have to worry about. I should have done this years ago.” His pathetic need to know why these women dumped him presumes that they owe him some kind of explanation, often at their own expense.

Now 20 years after the movie, High Fidelity has been rebooted as a 10-episode Hulu series centered around a woman—a woman named Rob (short for Robin). She’s played by Zoë Kravitz, who at least looks way cooler in a baggy leather jacket and beat-up Dickies tee than Cusack ever did. Still, I found myself wondering how the show would deal with the outdated aspects of its source material. Would Kravitz drop ugly truth-bombs about women in the same way that the book did about men, or be forced to turn her tastes into “Top 5” lists? And could this ode to music superfandom really get away with not acknowledging the advent of streaming?

Kravitz, it turns out, makes for a more dynamic, likeable Rob. She still owns Championship Vinyl, a perpetually empty used record store (this time in Brooklyn), where she employs two fellow pop-culture junkies who channel their passions in wildly divergent ways (Da’Vine Joy Randolph and David H. Holmes, both in heart-filled, star-making turns). Their world is strewn with useless trivia from the High Fidelity universe—the kinds of details these characters might obsess over, only turned into easter eggs: The main hangout is a bar named DeSalle’s, as in Marie DeSalle, the singer-songwriter character once portrayed by Kravitz’s mom, Lisa Bonet. The show’s musical canon centers around classic artists like David Bowie, who’s something of a spiritual guide to Rob, along with Prince and Fleetwood Mac. Echoing a memorable scene from the movie, there are multiple nods to folktronica group the Beta Band, as well as a moment where they remake said scene with a song by outsider icon Swamp Dogg.

There are other modern updates to key comedic bits as well, some more eye-roll-inducing than others. The out-of-touch dad who comes in looking for “tacky, sentimental crap” like Stevie Wonder’s “I Just Called to Say I Love You” for his daughter is replaced by a woman trying to buy Michael Jackson’s Off the Wall for her boyfriend. (Rob argues that it’s OK because the album is as much the work of producer Quincy Jones as it is MJ.) While debating whether to cancel great artists who did very bad things is indeed top of mind these days, it’s not exactly a discussion that lends itself to laughs. And just like the movie, there are direct quotes from Hornby’s book in the script (the author served as an executive producer, alongside Kravitz, the team behind Ugly Betty, and more).

The series opens a year after a devastating breakup, just as Rob’s putting herself out there again. Her ex Mac (Kingsley Ben-Adir) is back in town and engaged, which prompts a similar search for past relationship closure as the source material. In the beginning of the season, Kravitz’s character’s personality seems a lot like the Robs of the past: self-involved, secretly sentimental and not-so-secretly sad (there are so many shots of her poutily smoking and listening to records), equally terrified of commitment and loneliness. While Rob’s journey in previous versions offered only slight personal progress (with his off-on girlfriend Laura actually facilitating much of the change), Kravitz’s Rob shows the real-life challenges and vulnerabilities of self-improvement. By the last episode, she’s taken the first steps toward treating the people in her life better, and makes a decision that plants her firmly pointed forward.

A generous reading might consider the show a corrective to the original, particularly because women, people of color, and queer folks now work the stacks at Championship Vinyl. A more skeptical take is that even this well-meaning shift is morally suspect. As the New York Times’ Amanda Hess wrote two years ago of Hollywood’s thirst for gender-flipped remakes, “These reboots require women to relive men’s stories instead of fashioning their own. And they’re subtly expected to fix these old films, to neutralize their sexism and infuse them with feminism, to rebuild them into good movies with good politics, too. They have to do everything the men did, except backwards and with ideals.” Why spend all this time, money, and energy updating and changing the gender on source material that, in hindsight, is pretty dodgy about women? Is High Fidelity really so beloved (or its brand name so powerful) that they couldn’t have started from scratch on a series about music obsessives who aren’t exclusively straight white men? What is the point of paying homage to all this ephemera?

There’s a specific strain of toxic masculinity that lurks underneath the surface of, and is core to, the music fandom in High Fidelity. It’s the kind where men who struggle with conveying their feelings turn to their record collections as emotional support blankets. They dole out their music knowledge like baseball-card statistics and treat women as fair-weather fans who don’t even know the rules. (Many women critics I know prefer not to publicly rank their favorite music, which likely has something to do with how we’ve been condescended to in the past.) It doesn’t exactly help that the movie—arguably the first quintessentially ’00s-hipster rom-com—was successful enough to turn this argumentative mode of listenership into a full-blown cliché.

Reading High Fidelity recently, I noticed that nearly all the women characters were perceived as outside the realm of record-collecting. Love interests require a recalibration of taste (timid shop employee Dick’s new lady friend can’t possibly stay a Simple Minds fan), or a correction (Rob’s music journalist crush needs to be schooled on Top 5 list distinctions). Over the course of the book, Rob essentially schools girlfriend Laura to understand the differences between “good” pop music (“authentic,” soulful, largely old and American) and “bad” pop music (Tina Turner, Mike Oldfield’s Tubular Bells), distinctions that by today’s poptimist standards seem positively arbitrary. (Which the show, to its credit, appears to realize: Tina Turner’s Private Dancer is on display behind the cash register, alongside Jay Reatard’s Matador Singles ’08 and Tyler, the Creator’s Goblin.)

With all this in mind, it’s hard to even enjoy the series’ turning point, the moment when it dawns on Rob that maybe she shouldn’t be such an asshole. The realization arrives, like a seed being planted, at the end of the episode “Uptown,” which turns a five-page passage in the book and a deleted scene from the movie into one of the season’s centerpieces. A woman calls Championship Vinyl saying she’s selling a record collection, so Rob and her kinda-boyfriend Clyde (Jake Lacy) go uptown to check it out. The woman, a performance artist delightfully played by Parker Posey, is offering up her husband’s prized collection—likely worth tens of thousands of dollars—for a mere $20, as a conceptual stunt seeking revenge for his infidelity. Rob isn’t sure what to do, so she and Clyde go down to the fancy hotel where the cheating husband is staying, in an attempt to casually discover if this guy indeed sucks. Turns out he’s even worse than expected.

Played by Jeffrey Nordling, aka Laura Dern’s spectacular man-child of a husband in Big Little Lies, the dude is a total shitheel, replete with a midlife-crisis ponytail and a young girlfriend who doesn’t speak. He cuts off Rob at every turn, name-dropping rock stars and talking exclusively at Clyde. It all comes to a head when Rob challenges him on the release year of Wings’ live album Wings Across America; she knows it’s 1976. “No, sweetpea, you’re wrong,” says the smug jackass, who’s sticking by 1984 as the answer. What comes next is, briefly, one of the best moments in the whole first season: Rob flexes her knowledge by critiquing the LP’s backing vocal overdubs (“At what point is a live album not a live album?”) and praising its version of “Maybe I’m Amazed.” Kravitz plays it perfectly, meeting the man’s growing indignance with an unbothered coolness. Ponytail guy responds by turning to Clyde and saying, “You’ve got yourself quite a little firecracker there, don’t you pal? Word of advice: It’s all cute now but it gets old fast, trust me.”

Rob should absolutely buy this man’s records at a deep discount—both because she owns a freaking record store in this musical economy, and because he deserves it. But she bails at the last minute, telling Posey’s character that “music should be for everyone.” Really, as Clyde points out on the ride home, it’s because of her own fear that, if she’s bad enough, someone could take away her records, too. I suppose it wouldn’t be High Fidelity if it didn’t treat music fanaticism like the ultimate form of tribalism, but the show only adds fuel to the fire by making Rob’s adversary perfectly emblematic of a certain insufferable strain of wealthy, recreational music expert. The Robs of the past were showing off their collector code of ethics when they balked at the purchase, but Kravitz is motioning vaguely towards personal betterment. The “female” twist on High Fidelity? Growth and maturity.

Spread the word