I’ve been out in Los Angeles for the last few days, and the big economic problem here is the strikes against the movie studios, which have shut down production. More broadly, as I read the news, the biggest economic stories are the high cost of living, and then the United Auto Workers going on strike against the Big Three car companies.

The Washington Post had a good article asking workers why they are striking. Most cited inflation and fairness. “We’re not making enough money,” said Petrun Williams, a 58 year-old Ford repairman. “People should be able to buy their own houses, but right now it’s not possible.”

It’s a hard problem to tackle, because GM, Ford, and Stellantis are giant, wildly inefficient bureaucracies with high costs optimized to make $75,000 trucks, and electric vehicles are a completely different product. But “Bidenomics” isn’t necessarily helping.

In fact, Biden’s White House staff just doesn’t seem to have the capacity to hear what’s going on, or address it. Earlier this month, Biden gave a speech in Philadelphia celebrating Labor Day, and ahead of it, he said, “I’m not worried about a strike,” and “I don’t think it’s going to happen” — comments that are clearly a result of his senior staff giving him bad information.

These delusional comments prompted a Detroit Congresswoman to call up senior White House advisor Steve Ricchetti and scream, “Are you out of your f—ing minds?”

And this gets to a common question I hear in D.C., which goes as follows: Why is the public so unhappy? The economy looks, by most conventional measurements, as if it’s doing well.

The American Prospect’s Dave Dayen summarized the statistics as follows: Unemployment is low, inflation is down, consumer spending is rolling along, and certain manufacturing areas are booming. “Several measures,” he wrote, “like economic growth and prime-age employment, have actually rebounded to their trends from before the 2008 financial crisis, an almost unthinkable scenario just a few years ago.”

According to consistent polling, the public thinks inflation is high and getting worse, and that Biden has done very little to address any of their problems. What explains how the White House is floundering? One problem is plenty of people in the political class believe that the public is simply wrong to be angry.

Paul Krugman, for instance, wrote a New York Times column saying that normal people believe the economy is bad, even if it isn’t. I see White House officials interviewed on CNBC periodically, and while they don’t say that outright, it’s clear they think the economy is doing well and inflation is down, and their job is to sell their accomplishments.

There are two reasons why the White House simply cannot seem to govern effectively. The first is that the tools the political class uses to understand inflation are misleading them. The second is that Biden doesn’t have one unified policy agenda, but has a bunch of policy agendas that work against each other.

The result of these two factors is that Biden’s story — “look at all this prosperity I have delivered” — doesn’t work in the face of strikes and anger.

Sticker Price Versus Reality

Let’s start with why the White House doesn’t see a problem. It’s true that key members of Biden’s senior staff are mismanaging the situation, but that doesn’t explain why Krugman, as well as many economists in the administration, don’t see one either. Sure, you can look at individual strikes, but those are noisy events, not economy-wide developments.

How does the government perceive the experience of ordinary people in the economy? There’s a mess of information out there — what information matters, and what doesn’t? The President can’t ask 100 million Americans how they are doing before making a decision. Over the last century, bureaucrats have answered these questions by inventing a host of measurements to serve as a proxy for what normal people experience.

The government has been measuring prices using some variant of the Consumer Price Index (CPI) since 1913. When there’s a change to inflation, what that usually means is that the CPI is going up or down. And a change to inflation isn’t a change in absolute price levels. If inflation is, say, down, it doesn’t mean prices are down, only that the rate prices are increasing is less rapid than it was before.

Since 2021, prices have spiked fairly dramatically, with a CPI reaching up to 9 percent at certain points in 2022 before settling back to 3.7 percent last month. Once again, that doesn’t mean prices are down, just that the rate of increase is down. The crazy expensive fourteen-dollar sandwich is still a crazy expensive fourteen dollars, it’s just not going up to seventeen dollars. One of the bigger contributors to the CPI last month was housing, jumping by 7.3 percent over the past year.

But does the CPI really show how people experience price increases? After all, one of the most significant changes in what we pay is higher interest rates, which the Federal Reserve has hiked dramatically over the past few years. The Fed’s actions have increased credit card rates, mortgage rates, auto financing, and corporate and government borrowing costs. Surprisingly, none of this is directly included in our inflation metrics.

“The CPI’s scope,” writes the Bureau of Labor Statistics, “excludes changes in interest rates or interest costs.” The price of money, which is an input into everything, isn’t included in how we see inflation today.

That’s crazy.

When I was in the archives learning about Congressman Wright Patman, the Chair of the House Banking Committee in the 1960s and 1970s, I found that back then, people included the cost of interest rates in how they understood inflation. The 1960 Democratic Party platform discussed inflation in precisely this manner, saying that high interest rates enacted a “costly toll from every American who has financed a home, an automobile, a refrigerator, or a television set,” and was “itself a factor in inflation.”

This logic made sense. When you borrow to buy a car or a house, the cost of that car or house is your monthly payment, not the sticker price. But in the 1980s, the government changed its method of measuring inflation, so today, the CPI works under different assumptions.

So what does this change mean? Well, the two biggest purchases for an American family are a car and a house, and in both of these categories, the CPI excludes the key factor for normal people, which is how interest rates affect the monthly payment. The sticker price for a car is an important number, but it’s the monthly payment that matters.

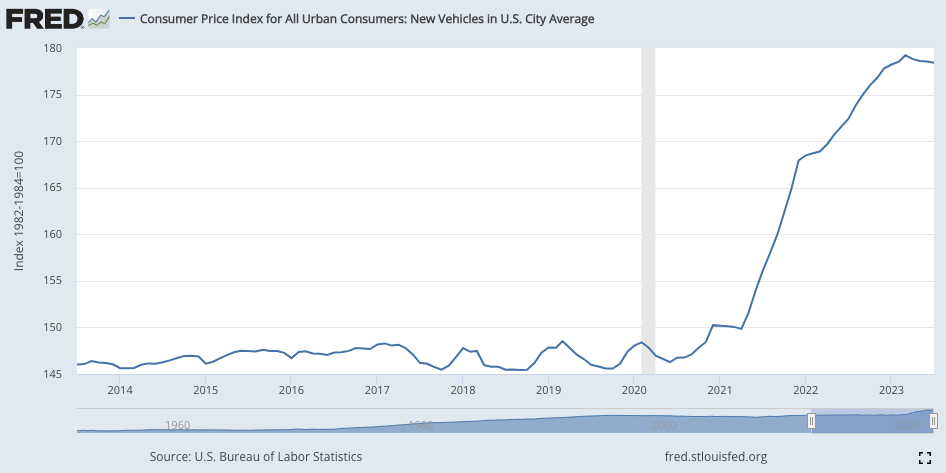

With that in mind, let’s take a look at the price of cars over the last ten years.

New car prices spiked from the beginning of 2021 to the end of 2022, but price levels are starting to come down, ever so gently. But is the monthly payment coming down?

No. According to Edmunds, in Q2 of 2022, the average monthly payment for a car was $678, in Q2 of 2023, it was $733. So there’s a slight price decline for the CPI as new vehicle pricing has come down, but there’s still an 8 percent inflation rate for what people actually pay.

Why are monthly payments going up if sticker prices are going down? It’s simple — the price of money has gone up. The average interest rate for a new car jumped to 6.63 percent in the second quarter of this year. It was 4.60 percent in Q2 of 2022, and 4.17 percent in Q2 of 2021.

And housing? Redfin, a real estate data website, reports the typical mortgage payment is up 20 percent from a year ago. And while most homeowners have mortgages they got prior to 2021, and so aren’t paying the higher prices, the exceptionally high current monthly payment means people can no longer move, and they have to watch their children struggle to find a place to live.

Housing prices are social, since the concept of home is so central to the American order. So even if you are financially unaffected, seeing a lot of people be unable to move, buy a home, or rent affordably gives everyone a sense of economic insecurity. That’s why striking auto workers mentioned the price of housing.

The calculation for housing in the Consumer Price Index is a bit more complicated than that for new cars, but the key piece to understand is that in 1983, the Reagan administration chose to exclude interest costs, instead asking homeowners what they think they would be paying in rent if they didn’t own the home they lived in.

The government simply “underestimates changes in housing costs,” according to an economist at Redfin, especially when interest rates are spiking. “And that’s because housing costs for the person who is actually active in the market experiences much greater fluctuation.”

The reason to change this measurement was so that inflation would look lower than it actually was. Over time, subsequent administrations sustained this shift. Lying about the symbols used to govern has a short-term political benefit in that it perhaps gets you some good media coverage — but over time, it means that the CPI for housing costs isn’t necessarily reliable.

So basically, the price of money is a big deal in terms of our experience paying for things, and it’s being excluded from the inflation metric that policymakers use to look at the economy. So that’s why policymakers are confused. Some of their key tools aren’t reflecting reality, and the people who originally broke the tools for political purposes aren’t there anymore.

Today’s political class doesn’t even know what they don’t know.

What Is Bidenomics?

Of course, housing and cars aren’t the only things people buy. Food is much more expensive than it was just a few years ago, as are everything from hotels to airfares to consumer packaged goods to seeds. I mean, Visa and Mastercard, which are barely affected by inflation, are jacking up their swipe fees to merchants.

None of that is a secret. The CPI for food shows that inflation might be coming down, but prices are still high. So what are Joe Biden and the Democrats in Congress doing about that? Well, White House officials call their plan Bidenomics.

The best way to explain Bidenomics is to listen to a judge Biden recently appointed to the D.C. district court, Ana Reyes, who was hostile to the Antitrust Division when they brought a case against two smart lock manufacturers.

Last month, Reyes sat on an American Bar Association panel where she attacked the idea of stronger antitrust enforcement, focusing specifically on her skepticism around labor-related claims. She bragged to the audience of defense attorneys that during the antitrust case she heard, she “pranked” government lawyers by spending three minutes pretending to dismiss their key witness, before saying “April Fools.”

“I have never in my life heard stunned silence,” she later said gleefully.

Having a corporate lawyer bully-turned-judge appointed by Biden killing an antitrust suit brought by Biden officials is a great example of Bidenomics, because it shows the lack of coherence of this administration’s policy. I’m a big fan of Federal Trade Commission Chair Lina Khan, but another Biden judge — Jacqueline Corley — allowed the largest big tech merger of all time, when Microsoft bought Activision, after Khan challenged the deal.

These judges matter in terms of inflation. Had Biden picked actual populists for the judiciary instead of Corley and Reyes, the White House’s ability to govern would look very different, and corporate America would be changing their pricing behavior due to fear of crackdowns. In early 2022, there was a flurry of interest in using antitrust to attack how corporations were informally colluding to raise prices. But an aggressive legal theory needs judges willing to take market power seriously, and Biden instead chose people who thwart his own administration.

It’s not just judges. Factions in the administration — in this case, the White House Council of Economic Advisors — explicitly opposed the corporate profit-inflation link.

I think a lot about antitrust, but the incoherence is systemic across most policy areas (and among Democrats in Congress). The pro-labor administration indicated support for the strikes in Hollywood against powerful studios, then a few months later the former White House Domestic Policy Council head — Susan Rice — rejoined the board of Netflix. For every attempt to make electric vehicles in America, there’s Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen pushing hard to ensure these cars are made abroad.

Normally, policy disagreements would be decided by the President and his staff. But Joe Biden is a procrastinator, and doesn’t like making choices. He’s also very old. As for his staff, well, while Biden’s former chief of staff Ron Klain was aggressive in terms of policy goals, his new chief of staff, Jeff Zients, is a relentlessly cheerful former management consultant wholly focused on process. Other important figures, such as Tim Wu and Brian Deese, have also left.

With Klain gone, there’s an insular clubbiness at the top, and an inability to provide a vision or pay attention to policy implementation. Even if you were to make the point that housing prices need attention, there’s just no one there who could or would do anything about it.

And that brings us back to the strikes. The Biden administration could have headed off the United Auto Workers labor action with discrete steps to help the workers, but the White House just doesn’t have any coherence. And so while Biden is saying pro-labor things and agreeing the CEOs are paid too much, there’s this.

There is also a sense among some Democrats and labor officials that Biden’s team miscalculated the standoff and hasn’t understood the severity of labor’s frustration or concerns. Even recent news that the Biden administration was considering providing aid to auto suppliers rankled some in the union world, who thought it could undermine the strike and saw it as evidence that there are always funds available for companies, but not workers.

This isn’t to say there aren’t significant achievements. Biden’s industrial policy push is real, with increases in investment in semiconductor production, electric vehicles, and batteries, as well new factories in general. His competition policy approach is also real, with new merger guidelines, as well as crackdowns on pharmaceutical profiteering and mergers, the prohibition of non-compete clauses, and the Google monopoly lawsuit.

There are routinely good decisions coming out from some of the regulators. The other day, for instance, the Department of Labor proposed a rule opening up 4 million more workers to overtime pay. Meanwhile, the Securities and Exchange Commission has begun a crackdown on private equity.

Unlike the Obama administration, which was ideologically oriented to push wealth and power upward, the Biden administration has a few populists trying to do the opposite. But in an inflationary environment where the stats are juiced to mislead policymakers, that’s not good enough.

What Happened to Biden’s State of the Union?

In February, Biden gave a State of the Union speech focused on making things in the U.S., going after junk fees, and taking on corporate power. His polling temporarily spiked. Since then, there has been no messaging follow-up from the White House on anything he said in that speech, almost as if Zients and the rest of the White House were embarrassed that Biden put forward a populist set of arguments.

Instead, various officials are out there on TV saying “look at these charts!” They want credit for inflation being down, economic growth being up, and unemployment being low. But without recognizing that the actual costs of housing and transportation are increasingly unaffordable and going up, that just looks weird.

Moreover, there’s no actual policy regime, just a disjointed set of factions trying to get as much done as possible according to their preferred view. It’s mostly unclear how Biden is actually affecting people’s lives, and it’s only the genuinely organized groups of workers who are showing that things aren’t okay.

The economy isn’t great, and there’s no point in trying to pretend it is.

That said, Biden can save his administration. He has accomplishments, and his State of the Union messaging resonated. He can argue that his first term was about having America recover from COVID-19 by re-shoring factories, restoring full employment, and fixing supply chain problems. He can brag about all the big companies suing him, like various pharmaceutical firms mad that the White House is imposing price caps. Then he can pledge that he’ll focus on bringing down housing costs in his second term.

Will such a story work? I don’t know. Maybe the current pitch will work; in the 2022 midterms, Biden out-performed expectations. But the alternative would at least be more relatable than “Eat some charts!”

If you want to read more articles like this, subscribe to BIG, Stoller’s newsletter on the politics of monopoly power.

Spread the word