Elmore Nickleberry, one of the last living participants in the Memphis sanitation workers’ strike of 1968, a historic walkout that sought to win respect and equal rights for African American workers and that drew the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King to their side, died on Dec. 30 in Memphis. He was 92.

His death was confirmed by his wife, Mary Nickleberry.

Mr. Nickleberry was one of 1,300 sanitation workers who joined the 65-day strike, which culminated in a major civil rights and labor union victory, albeit at a tremendous cost — Dr. King was assassinated while he was in Memphis to rally behind the strikers’ cause.

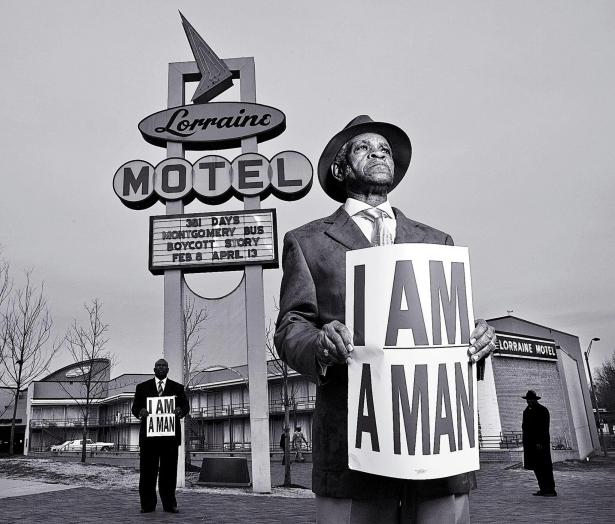

The sanitation workers, nearly all of them Black, were protesting low pay, poor working conditions and demeaning treatment. “Everybody called us ‘boy,’” Mr. Nickleberry said in a 2014 interview. “The supervisors also called us ‘boy.’ You’d tell them, ‘I ain’t no “boy.” I am a man.’ And they’d keep calling you ‘boy.’”

Image

Workers protesting during the Memphis sanitation strike in 1968. Credit...The Withers Family Trust/BAM

Memphis sanitation workers in those years used round 17-gallon plastic tubs to haul garbage from backyards to trucks on the street. Like his co-workers, Mr. Nickleberry would fill his tub with 30 or 40 pounds of garbage and carry it on his back, shoulders or head.

“There would often be holes in the tub,” he said, “and the garbage and maggots would crawl down your back and onto your clothes.”

No matter how dirty and sweaty they were, the trash collectors weren’t allowed to shower in the sanitation depots. “We smelled real bad,” Mr. Nickleberry said. “Nobody wanted to sit near us” on the bus ride home. He usually walked the six miles instead. Arriving there, he said, “I’d take my clothes off in the backyard because I stink so bad.”

On Feb. 1, 1968, two Memphis sanitation workers, Echol Cole and Robert Walker, were sitting in the back of a garbage truck to escape a downpour when a malfunction caused the compactor to suddenly start running. It crushed them to death. The tragic mishap was a catalyst for the strike, which began on Feb. 12.

The work stoppage was further fueled by frustration over the Memphis mayor’s steadfast refusal to recognize the workers’ union, which was part of the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees.

When the strikers held their first march, on Feb. 23, the police attacked them with batons and mace. “The police started whupping us,” Mr. Nickleberry told The Memphis Commercial Appeal in 2018. “I got hit hard.”

The strikers marched week after week, but the mayor, Henry Loeb, wouldn’t budge. He said it was illegal for city employees to strike and insisted that he would not bargain “with anyone who was breaking the law.”

To pressure him, the strikers enlisted support from union and civil rights leaders from across the country. Dr. King saw his involvement as part of his Poor People’s Campaign, an effort to pressure Congress to create more jobs and housing for thousands of economically disenfranchised people.

At the time, Mr. Nickleberry, who had been a sanitation worker for 14 years, earned $1.65 an hour (a little under $15 in today’s currency), just five cents above the federal minimum wage at the time. Forty percent of the trash collectors’ families fell below the poverty line; many qualified for welfare and food stamps.

Image

Memphis sanitation workers marching past the Tennessee National Guard in 1968 during the strike, which lasted 65 days. Credit Charlie Kelly/Associated Press

Dr. King was killed on April 4, the day after he gave his “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” speech in Memphis and four days before he was to lead a massive march in support of the sanitation workers. With the nation rocked by the assassination, President Lyndon B. Johnson intervened to settle the strike, dispatching James Reynolds, the under secretary of labor, to Memphis.

Mr. Reynolds succeeded in pressuring city officials to reach a settlement that recognized the union and included raises and strict protections against racial discrimination, which meant that Black trash collectors could finally earn promotions.

“We got a good raise,” Mr. Nickleberry said. (He received a raise of 15 cents per hour, a 9 percent increase.) “We got showers. We got better working conditions. We got health benefits.”

Most important, Mr. Nickleberry said, the workers won dignity. “The union came in and we got respect,” he said. “They stopped calling us ‘boy.’ They started calling us ‘A Man. A Sanitation Man.’”

Elmore Nickleberry served in the Korean War in the Army’s Eighth Armored Division, rising to corporal. He was dismayed, however, by how he, a war veteran, was treated on returning to his hometown in 1953. “They treated me better overseas than I was treated in Memphis,” he said.

With Jim Crow laws making it hard to find work, he settled for a sanitation job, starting at 75 cents an hour. He said he hated it when homeowners called him “garbage man,” as if he himself were just garbage.

Mr. Nickleberry married Mary Lewis Ray in the early 1960s. In addition to his wife, he is survived by six children, Mitchell Cheryl Carr, Toyia Polk, Zakeyia Johnson and Terence E., Stanley and Tanya Nickleberry; 18 grandchildren; and five great-grandchildren. Another daughter, Tondalaya, was murdered in 1999 at 19 when a man whom she thought was a friend strangled and stabbed her multiple times, according to The Memphis Commercial Appeal.

Mr. Nickleberry said he continued working into his 80s because the 1968 settlement had left the workers without pension benefits. “I had to feed my family,” he told The New York Times in 2017. “That’s why I stayed.”

Mr. Nickleberry remained a strong union supporter throughout his life. “If we didn’t have a union, we would get nothing,” he said in 2014. “We’d be in the same shape as before. You got a union to back you, you achieve more.”

Spread the word