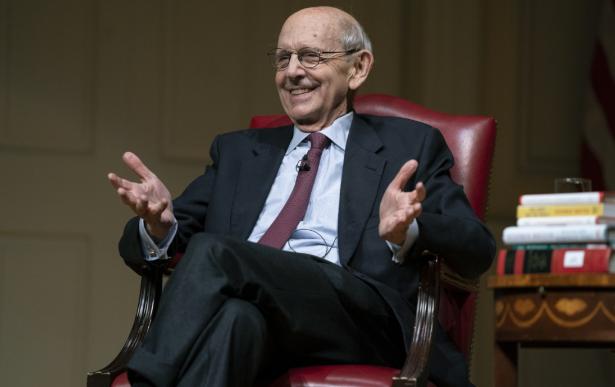

Earlier this week, retired Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer penned an op-ed in The New York Times about friendship among the court’s justices. And about collegiality. And about not letting professional disagreements interrupt their wife-swapping during card games.

The title of the piece is “The Supreme Court I Served On Was Made Up of Friends,” and it pretty much went downhill from there. It’s mainly just a few anecdotes from Grandpa Breyer about how nine people who work together for life can enjoy each other’s company. It’s about how some of the justices used to play bridge together, while others went to the opera, and how they would share jokes over lunch. There’s a particularly insipid story about the reason former Chief Justice William Rehnquist put literal gold stripes on his robe, which Breyer tells us was inspired by the Gilbert & Sullivan musical Iolanthe. I guess that makes sense, considering Iolanthe is about a fairy queen who is going to murder everyone she loves because the law says that fairies who marry men must be put to death, but she’s stopped when a man suggests changing the law to compel fairies to marry men in order to live. “Death or marriage” is an adequate summary of Rehnquist’s approach to women’s rights.

Reading the piece quickly, a person might be inclined to regard Breyer’s op-ed as “well meaning” or at least “harmless” drivel. We’re clearly supposed to think, how nice, how quaint! Why can’t we all just get along the way the justices do? And, in fact, Breyer closes by advising, “What works for nine people with lifetime appointments won’t work for the entire nation, but listening to one another in search of a consensus might help.”

It’s the kind of conclusion one would expect from a fairy, not an intellectual who has been paying attention. Breyer’s article doesn’t offer any actual evidence to show that consensus is possible—or even desirable given what some of his work “friends” want to do to vulnerable people in this country. Moreover, Breyer fails to mention that his precious comity and consensus-building failed to stop his conservative friends from gutting the Voting Rights Act in 2012’s Shelby County v. Holder or revoking reproductive rights in 2021’s Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health.

The point of Breyer’s piece (to the extent there was a point) was to distract readers from those decisions (and any number of horrid decisions emanating from the corrupt and broken Supreme Court) and burnish the institution’s reputation at a time when the people have just about had enough of the justices. The Supreme Court’s approval ratings hover at all-time lows, and every month there is another story, order, or opinion that exposes the court as a partisan cabal beholden to the Republican Party or the conservative culture warriors. The Roberts court is a Moloch set on devouring the rights of women, people of color, and the LGBTQ community, while preserving the rights of mass shooters to amass deadly arsenals, but Breyer wants us to know that “in my 28 years on the court I did not hear a voice raised in anger.”

Why the hell not? Why weren’t you, Steve, sitting there screaming at your conservative colleagues, or asking everyone who would listen to stop your “friends” from hurting people? Why do you think intellectual detachment in the face of active horror is a virtue, when it’s more like a sin? Why do you think the loss of public decorum is a bigger threat to the Supreme Court’s institutional standing than its self-inflicted loss of ethics, impartiality, and accountability?

In service of this reputation-burnishing, Breyer works overtime to try to humanize the justice—to get people to see them as regular people, not nuclear weapons deployed against fundamental rights. As columnist Hayes Brown explains, the “core” of Breyer’s essay “emphasiz[es] the humanity of justices who are more than willing to de-emphasize the humanity of others in their decisions.” Breyer’s task would be a lot easier, however, if the justices themselves treated people as human beings, instead of mere pawns in their ideological wars.

Consider the last few years: Since 2022 alone, the Supreme Court justices have decreed that pregnant people can get sick and die for the sake of “state’s rights,” that immigrants can be harassed and terrorized for lack of “status,” and that inmates can be sent to their deaths because evidence of their innocence was not brought in a “timely” manner. Where is the humanity when desperate people show up for relief but are told that James Madison and Harlan Crow want them to suffer?

Maybe Breyer can enjoy a night at the opera with people who think a 10-year-old girl can be raped and forced to bring the pregnancy to term as a matter of law, but I can’t. There isn’t a flute magical enough to make me like these people. Maybe Breyer should have spent less time having lunch with his conservative colleagues and more time having lunch with their victims.

Breyer’s piece, of course, wasn’t written for me, or for anybody who has to fight against the edicts handed down by his conservative friends. But I am curious about whom his piece was written for, and why The New York Times was eager to publish an editorial that adds functionally nothing to the discourse.

The most simple (and cynical) answer is that Breyer has a new book out: Reading the Constitution: Why I Chose Pragmatism and not Textualism. I haven’t read it yet, but all of Breyer’s prior books (and most of his judicial opinions) follow the same pattern of moderate pablum filtered through a law and economics prism. They are, in a word, boring (and I say that as a person who is generally not bored by the law). The New York Times review described this latest one as “well meaning, tedious and exasperating.” The reviewer also said that Breyer is “so wedded to propriety and high-mindedness that he comes across as earnestly naïve,” and I think that pretty much summarizes his op-ed. Well-meaning naivety is kind of Breyer’s calling card at this point, so if you liked his op-ed, you’ll probably love his book.

There is certainly an audience for Breyer’s brand of earnest high-mindedness in the face of all available evidence to the contrary, and that audience probably makes up the irreducible core of New York Times subscribers. There are a lot of people who believe that “politics” and “policy differences” can and should be ignored among colleagues and friends. They believe that the fact that one person supports, say, amnesty for migrants who are out of status, while another person supports shooting them to death should their children miraculously manage to squeeze through the razor wire barricade erected to drown them, shouldn’t prevent those two people from enjoying a few beers together. They believe that rancor is the thing that is odious, and if well-meaning people would just sit together and listen to each other, we could find common ground between the “Black people are genetically dumber and more prone to violence than whites” crowd, and the “I have read books about the history of Western Europe” crowd.

The audience for Breyer’s anecdotes is likely the same demographic as Breyer himself: old straight white college-educated men, and people who desperately want to attain the status and prestige of old straight white college-educated men. Breyer can maintain the intellectual gooberism of institutional collegiality in the face of real-world harms because the harms are not visited on him. He’s not the guy the cops choke to death; he’s not the immigrant being deported away from his children; he’s not the woman being forced to incubate a rapist’s baby against their will. Breyer was a reliable liberal vote on all of these issues, but he can write about people who disagree with him from a detached, pragmatic viewpoint, because these human rights violations aren’t happening to him and never will. He can hang out with his colleagues despite their worst rulings, because their worst rulings are always affecting other people.

Indeed, there is evidence that when issues hit a little closer to home, a different Breyer emerges. Despite his reputation as a moderate liberal (as well as his well-earned anti–death penalty bona fides), Breyer was a hard-liner when it came to criminal justice issues. Cristian Farias has written: “No liberal justice has cast more pro-government, carceral votes than Breyer has in the modern Supreme Court.” That’s true, but Breyer wasn’t always that way. Breyer turned into a full enemy of Fourth Amendment and its protections against unreasonable searches and seizures kind of late in the game, in 2013. I’ve always believed that had a lot to do with his being robbed by a man wielding a machete while on vacation in the Caribbean in 2012. I think Breyer proves the old adage “a conservative is a liberal who got mugged the night before.”

I do not believe Breyer ever invited the guy who robbed him back to his house to play bridge. Maybe Breyer wishes he could have. Maybe Breyer believes they could have reached a consensus on how much cash and jewels Breyer should have handed over. But maybe if Breyer understood that his conservative colleagues are robbing people not of their wallets but of their fundamental human rights, he’d exhibit better judgment in his choice of friends.

I understand that the Supreme Court justices can put aside their professional differences long enough to play cards together. What Breyer doesn’t seem to understand is that many of us, those not clad in gold-fringed robes and unaccountable power, cannot merely set aside the justices’ adverse rulings. We have to live with them. We have to suffer under them. And some of us have to die because of them. Perhaps Breyer could be bothered to remember that the next time his buddies come over for dinner.

Elie Mystal is The Nation’s justice correspondent and the host of its legal podcast, Contempt of Court. He is also an Alfred Knobler Fellow at the Type Media Center. His first book is the New York Times bestseller Allow Me to Retort: A Black Guy’s Guide to the Constitution, published by The New Press. Elie can be followed @ElieNYC.

Copyright c 2024 The Nation. Reprinted with permission. May not be reprinted without permission. Distributed by PARS International Corp.

Founded by abolitionists in 1865, The Nation has chronicled the breadth and depth of political and cultural life, from the debut of the telegraph to the rise of Twitter, serving as a critical, independent, and progressive voice in American journalism.

Please support progressive journalism. Get a digital subscription to The Nation for just $24.95!

Thank you for reading The Nation!

We hope you enjoyed the story you just read. It’s just one of many examples of incisive, deeply-reported journalism we publish—journalism that shifts the needle on important issues, uncovers malfeasance and corruption, and uplifts voices and perspectives that often go unheard in mainstream media. For nearly 160 years, The Nation has spoken truth to power and shone a light on issues that would otherwise be swept under the rug.

In a critical election year as well as a time of media austerity, independent journalism needs your continued support. The best way to do this is with a recurring donation. This month, we are asking readers like you who value truth and democracy to step up and support The Nation with a monthly contribution. We call these monthly donors Sustainers, a small but mighty group of supporters who ensure our team of writers, editors, and fact-checkers have the resources they need to report on breaking news, investigative feature stories that often take weeks or months to report, and much more.

There’s a lot to talk about in the coming months, from the presidential election and Supreme Court battles to the fight for bodily autonomy. We’ll cover all these issues and more, but this is only made possible with support from sustaining donors. Donate today—any amount you can spare each month is appreciated, even just the price of a cup of coffee.

The Nation does now bow to the interests of a corporate owner or advertisers—we answer only to readers like you who make our work possible. Set up a recurring donation today and ensure we can continue to hold the powerful accountable.

Thank you for your generosity.

Spread the word