If we could go to Cuba right now, as I was telling an audience in Des Moines recently, one of the first things we’d notice is that our island neighbor nation is, like us, preparing to celebrate the special religious holidays that are upon us.

It will probably come as a surprise to many of you that religious and church life in Cuba is thriving, and has been since the 1990s.

There’s a story in that, something I unexpectedly stumbled on in my 2017 visit to Cuba. And it’s a key part of the speech I gave on my lifelong interest in relations between the U.S. and Cuba, to members of the 133-year-old Prairie Club. It meets monthly to consider serious academic-like papers by one of the group.

The story I began with involves the Rev. Raul Suarez, now 88 years old, pastor emeritus of Ebenezer Baptist Church in the Marianao neighborhood of Havana.

In 2017, a group of us from Plymouth Congregational United Church of Christ, where Mary Riche and I are members here in Des Moines, were lucky enough to meet and visit at length with Suarez. Ebenezer Baptist and Plymouth Congregational, for seven years now, have been sister churches, with lots of interaction between them.

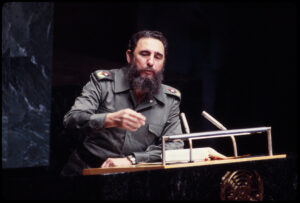

Suarez, for 25 years stretching from last century to this one, was an elected member of the Cuban National Assembly – its parliament. He knew and worked with Fidel Castro.

In fact, Suarez saw Castro rise from promising young athlete, to young lawyer, to para-military guerilla fighter, to revolution leader, to prime minister, and eventually president of Cuba and chairman of the Communist Party of Cuba. Castro died in 2016.

Back to the story of Christmas coming to Cuba – or rather, Christmas returning to Cuba.

I have to set it up by reminding you that after the Cuban revolution, which Castro led in the 1950s and finally won in 1959, organized religion was banned.

He declared the nation to be “atheistic.” Churches closed.

Pastors like young Suarez and his brother-in-law the Rev. Paco Rodes either left the country or were assigned, like so many other Cubans, to manual labor jobs on sugar canes farms or other industries that had been “nationalized.” That means their ownership was taken away from the private businesses, many of them American, and were now being overseen by government and Communist Party officials.

In 1960, U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower retaliated by ordering an economic blockade of Cuba, hoping it would eventually cause regime change.

Amazingly, that blockade continues today – and so does the Communist regime. It is now headed by President Miguel Díaz-Canel, who wasn’t born until the year after the revolution, isn’t related to the Castros and was never in the military.

What the blockade really did, initially, was lead Cuba to the old Soviet Union for help. That alliance gave Cuba essential supplies like oil, gas, food, medicine – as well as for leadership and military protection.

That went fairly well, until 1991, when the Soviet Union crumbled under the weight of its own ineffective bureaucracy and bullying.

Cuba’s economy, without its main supplier, essentially collapsed. People today refer to the decade that followed as the “Special Period.” People starved, even the state-supported businesses failed, and tourism stopped.

“When the economy went through the floor, there were terrible, terrible times in Cuba,” recalled Rev. Rodes, now a retired Baptist minister in the city of Matanzas, 50 miles east of Havana, when he talked to our Plymouth group in 2017. “People needed hope. They needed the church.”

His brother-in-law Suarez, the Baptist pastor over in Havana, was also then the head of the Cuba Council of Churches, which was essentially an underground organization. Suarez had personally known Castro since 1984.

He wrote to Castro in 1991 and asked for a meeting, and they had one, then another, then another. Suarez hit hard on the idea that Cuba’s Christian churches – if they’re indeed following the principles of Jesus Christ – “are as revolutionary as the government is,” as he recounted for us.

Castro, who had been educated in Catholic Jesuit schools in Cuba, listened and actually agreed. That led to a two-day, nationally televised conference with newly energized pastors talking about the earlier repression and what renewed spiritual life could do for Cubans.

Castro, in fact, subsequently ruled that the repression of religion had been an “Error of the Revolution.”

A year later, the Cuban constitution was amended, making the government “secular” rather than “atheist” and granting religious freedom.

And, as I said, there has been a reemergence of church life, in almost all faiths. In recent years, the evangelical mega-churches have really grown in Cuba, just as in the U.S.

All that changed the ministries of Rodes, Suarez and other pastors for the second half of their careers.

“Really, it felt like we got to start living in a different country,” Rodes said.

Added Suarez: “A big part of my life since then has been teaching Marxists and Communists that you could be as revolutionary as they were, while still worshipping in your church. And I taught Marxists and revolutionaries that they could be involved in church, too.”

Then in late 1997, Castro summoned Suarez back to his headquarters for another meeting.

Suarez said the president told him, “I want you to tell me again the story of Christmas,” which Castro remembered from his youth but had forgotten much of the biblical story. He invited Suarez to his headquarters for one of the late-night dinner events for which the Cuban leader became known.

Over dinner and drinks – “starting very late at night and going on until the early morning hours” – Suarez told the story of the birth of Christ.

Days later, just before Pope John Paul II visited Cuba in January 1998, Castro “reinstated” Christmas as a national holiday – and Cubans have been joyously celebrating it ever since.

The banning of Christmas, Castro later often said, was another “Error of the Revolution.”

Can I share one more of those errors?

When you visit Cuba now, you see crowds flocking to John Lennon Park in a nice section of the capital city of Havana, to sit on a park bench next to a life-size statue of the former Beatle, getting their photos taken. I don’t believe John Lennon ever traveled to Cuba, and I’m certain the Beatles never performed there.

So, why is there now a statue of Lennon here, and why is that a big deal?

In about 1963, when Beatles mania swept the world, their music was banned from Cuba. Castro back then dismissed the British rock band’s music as a “bad bourgeois influence,” especially on young people.

If you try to ban young people from experiencing something, you know what happens. Predictably, Beatles music became “like forbidden fruit,” Cuban friends told us, and for decades, kids played and traded boot-legged records, tapes and CDs of the Beatles. Eventually, the kids became adults, and they are still playing their Beatles music.

By the year 2000, Castro, then 74 years old, decided to make things right. He formally rescinded the Beatles ban, had John Lennon Park built, including the impressive statue of Lennon by a leading Cuban sculptor.

At a dedication ceremony, Castro sat next to John Lennon’s son Julian, also a musician, and afterward the Cuban leader praised the Beatle to the press: “What makes John Lennon great in my eyes is his thinking, his ideas. I share his dreams completely. I too am a dreamer who has seen his dreams turn into reality.”

But what of the earlier ban? Oh, Castro said, that had been another one of those “errors of the revolution” that occurred.

It took 30 years for the Cuban government to start admitting such errors.

Ever since, Cuba has changed – a lot.

I frequently have to remind myself that it is a very small place, especially for the prominence it has had in world affairs over the past 65 years.

The island nation is 780 miles long, 119 miles wide at its widest, 19 miles wide at its narrowest, for 42,426 square miles. The state of Iowa, for comparison purposes, has 56,272 square miles. Total population of Cuba is 11.2 million, more than three times as many people as Iowa has. (But the Iowa statistic that Cubans all seemed to love hearing when I was there was that, while we have only 3 million people, we have more than 22 million pigs. Cubans, who love pork, were astounded.)

It turns out that many if not most of our own nation’s policies toward Cuba have been wrong-headed, ineffective, even counter-productive. Call them our own errors of the Cuban revolution.

Particularly, our blockade of trade with Cuba is directly or indirectly responsible for a whole lot of misery there, especially right now. Our policies have really only been successful in inflicting cruelty on the people of Cuba, most of whom are choking in poverty, crumbling infrastructure and other second-rate service from their own government.

It is high time for us to be better neighbors.

[Chuck Offenburger, of Jefferson and Des Moines, has been writing about Iowans for 62 years (he started as a sportswriter when he was 13 in his hometown of Shenandoah). He’s been wearing his trademark black & white saddle shoes even longer than that. For 26 years, he wrote the “Iowa Boy” column and other stories for the Des Moines Register. He was co-host of RAGBRAI – the Register’s Annual Great Bicycle Ride Across Iowa – for 16 of those years. He was also well-known for his coverage of the Persian Gulf War in 1990 & ’91, the career of Iowa-born opera great Simon Estes, and his Top Ten rankings of Iowa’s best cinnamon rolls. He writes the "Iowa Boy Chuck Offenburger" blog and is a member of the Iowa Writers' Collaborative.]

Spread the word